The salt pulse brings ocean water to the deep basins

The water in the Baltic Sea exchanges only weakly and remains low-salinity brackish water. Only rarely does a very large amount of saline ocean water flow into the Baltic Sea in a short period. This situation is called a salt pulse. Salt pulses oxygenate the deep water areas of the Baltic Sea but may also intensify eutrophication.

Saline North Sea water reaches the Baltic Sea through only one route: the Danish straits. However, the straits are narrow and shallow, which limits the flow of dense seawater into the Baltic Sea. Mostly, low-salinity water from the Baltic Sea flows through the straits, mixing with surface ocean water in the Skagerrak and the North Sea.

Significant amounts of saline ocean water only enter the Baltic Sea when weather conditions are just right for an extended period. These periods are short, lasting only a few weeks, and are known as salt pulses.

Only a strong salt pulse renews the deep waters

Large salt pulses occur infrequently, perhaps only once or twice a decade. During such a pulse, a very large amount of North Sea water, 200–300 cubic kilometres, enters the Baltic Sea. Although large salt pulses are rare, they are crucial for the well-being of the Baltic Sea. They bring new oxygen-rich water to the deep basins of the Baltic Sea.

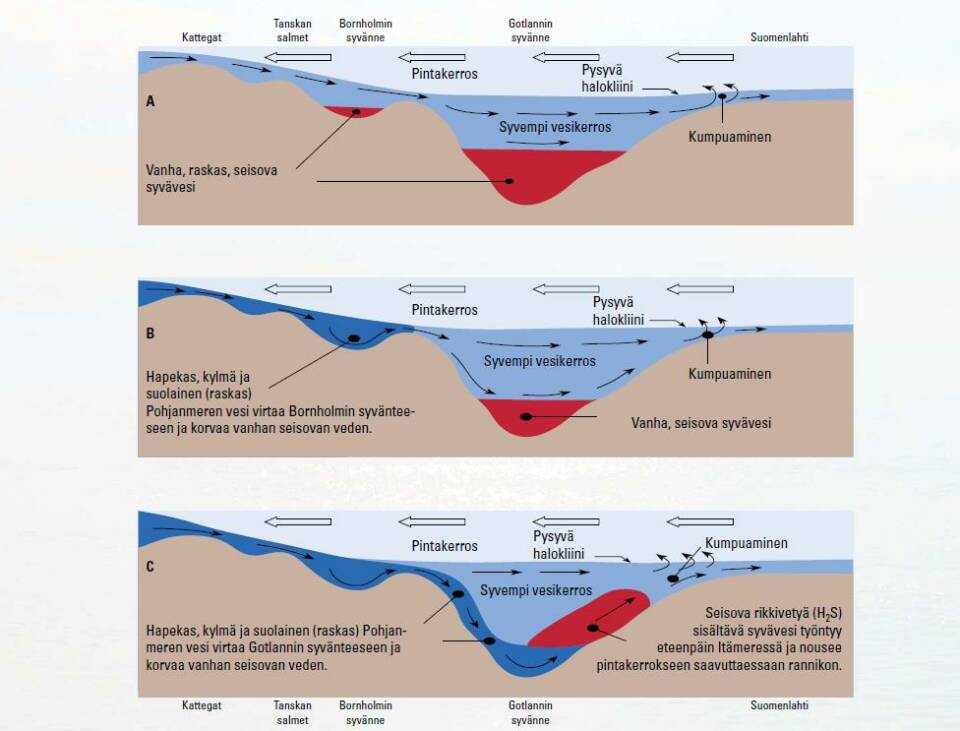

A: Brackish water, which is less saline than North Sea seawater, flows constantly out of the Baltic Sea. At the same time, smaller amounts of saline North Sea water flow into the Baltic Sea to the deeper layers. This weak inflow does not reach into the large depressions and thus does not oxygenate them.

B: The North Sea often produces moderately intense saltwater inflows that do not extend to the Bornholm Basin.

C: Instead, a strong inflow, i.e. a large saltwater pulse, is able to displace the old nutrient-rich and anoxic water within the Gotland Deep. When displaced by oxygenated and saline water, the deep water is set in motion, eventually reaching the shallow coast where saline and nutrient-rich old water rises to the surface.

Salt pulses have both positive and negative effects

When a major Baltic inflow penetrates the Baltic Sea, it raises the salinity of almost the entire area. The distribution of many plant and animal species changes according to their salinity requirements. Many planktonic marine species spread north- and eastwards.

As deeper oxygen conditions improve, benthic organisms may reconquer areas previously dominated by macroscopic fauna. In addition, cod can also spawn further north, even in the Gotland Deep, which is an important spawning ground when oxygen conditions allow.

Major Baltic inflow may also have negative effects. Eutrophication intensifies when nutrient-rich deep-water mixes with well-lit surface layers in which primary production occurs.

The saline, low-oxygen deep water originating from the bottom of the main Baltic Sea is pushed onwards and can eventually settle into the basin of the Gulf of Finland, even to its easternmost parts. In this case, the low-oxygen water strengthens the halocline, the salinity stratification layer, in the deep basins.

The halocline forms a floor preventing the wind from mixing oxygenated surface water with bottom water. Thus, a powerful halocline can lead to the deoxygenation and internal loading of the seabed as nutrients are released from the bottom sediment.

Salt pulses occur randomly

The conditions for a large salt pulse are most favourable during winter storms. Everything aligned in the winter of 1951, when a very strong and large salt pulse entered the Baltic Sea. A similar large salt pulse was also observed in the winter of 1975–1976.

There were several smaller saltwater pulses in the 1970s, but the next significant salt pulse did not occur until 1993. It was the first to break the stagnation of the deep waters, a phase of standing water that had prevailed in the Baltic Sea since the 1970s.

Since the turn of the millennium, there have been a few large salt pulses: in 2003 and 2014. The latter was the third largest pulse ever, followed by medium-sized pulses in 2015 and 2016. In 2023, another medium-sized salt pulse arrived. However, during the long period of standing water, the oxygen deficiency in the deep waters of the Baltic Proper had become so severe that even these pulses only slightly and temporarily improved the situation.

A graph of the amount of salt flowing into the Baltic Sea can be found on the Finnish Meteorological Institute’s website.

Ilmatieteen laitos: suolapulssit (in Finnish)(siirryt toiseen palveluun)

-

Find out more

Find out moreSalinity

-

Find out more

Find out moreAnoxic bottoms